In an age where the benefits of “embodiment” are eulogized across various disciplines, from movement therapies to cognitive science, the idea of becoming more attuned to our bodies holds undeniable appeal. Movement practices such as dance make us more “embodied,” don’t they? But what if creative use of movement can also “disembody” us, suspending our embodied awareness? This is precisely what happened during my encounter with the dance performance “Les jolies choses” by Catherine Gaudet.

On a late July evening in 2024, Patrick Oancia and I attended the performance at Théâtre de Verdure in Parc La Fontaine, located in the heart of Montréal’s Plateau. We had no prior knowledge of the piece, and I surely wasn’t anticipating how profoundly it would impact my perception, leading to a temporary feeling of disembodiment. This article explores the nuances of that encounter, in all its peculiar counter-intuitiveness, while reflecting on topics at the intersection of movement and cognition.

Table of Contents

What I saw

The performance takes place in late July at an outdoor theater. It’s just after sunset, dark. The audience is told not to film.

The performance begins. On stage, five people—three men and two women—stand still in a circle. They are silent. No music plays. Then, one woman starts a subtle, repetitive movement—knees flex, arms flex, relax. Knees flex, arms flex, relax. Barely noticeable at first, the movement repeats and grows in amplitude. This goes on for a few minutes in silence. Gradually, music joins in, in sync with her movements, a clear clock-like beat. Each beat is marked by a syllable “tu” in a high-pitched female voice, like an organic metronome.

One of the male performers starts moving his wrist in sync with the music. After a few more minutes, the remaining dancers join, each with a distinct repetitive movement. Some rotate their torsos, sharply turning left and right with arm movements. Sometimes, all five perform different movements. Other times, two or three synchronize, only to go out of sync again. This progression is unpredictable, gradual.

They rotate in place. Then, they slowly move across the stage. After about 15 minutes, they form a line. For the remainder of the performance—about an hour—they move with the music, turning around a central figure like a clock with two opposing hands.

As the line turns counterclockwise, the five continue in sync, performing movements that evolve. Occasionally, one dancer diverges with a drastic change, or they introduce variations. The movements become very dynamic and cardiovascularly demanding. Sometimes, the dancers scream as if to communicate. As the performance nears its end, movements and music grow more and more cathartic. In the end, they move into a tight circle. After more catharsis, the movements slowly die down. So does the music.

You can watch a fragment of this performance above. The video allows to hear the music and captures the performance’s later stages. However, the camera’s movement creates a very different experience compared to viewing from a static position in the audience.

What I felt

The performance undeniably presented some social metaphors—questions of individuality versus the collective, authentic desires versus obligations, being bound by versus trying to escape habits, and distinctly organic cyclicity and development. Yet, these interpretations felt secondary to the visceral perceptual impact.

I don’t recall ever experiencing a performance so utterly attention-grabbing. I couldn’t take my eyes off the stage—and it seemed like many people in the audience felt something similar.

Typically, watching a performance feels like a conscious act of will. I actively choose to stay engaged, retaining the peripheral awareness of my surroundings, thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations. Yet, this time, following the gradually developing minimalistic patterns unfolding on stage heightened anticipation to the point where it felt like I needed to know what was going to happen next.

Without deciding to do so, I found myself absorbed in trying to notice when the movements synchronized and when they drifted apart. The slow, incremental, barely detectable evolution of these movements couldn’t be detected with peripheral vision and, therefore, the essence of the scene couldn’t be captured with routine, subconscious visual scene processing that automatically alerts you, “catching” your conscious attention. Instead, I had to deliberately scan the scene, shifting the gaze from performer to performer, looking for salient features. Basically, I had to use mental energy to consciously do what’s normally handled unconsciously, with much lower energy demands. It was unclear what the “main” object was, nor was the scene itself the main object.

You may be familiar with the “invisible gorilla” experiment, demonstrating the selectiveness of awareness. When we are focused on something, we can easily miss something else, even if outrageously unusual and out of place. And the “invisible gorilla” example features only 2 things.

Yet, the performance had five people. And their movements were constantly changing. Besides, unlike in the gorilla experiment, nobody gave any directions about what to focus on. Because of the repetitiveness of the movements, evolving so slowly, it required an enormous amount of concentration to keep noticing them. Yet, every time I finally noticed a change in pattern, it felt rewarding, so I kept doing it. And as this required further concentration—intense steady concentration for one hour straight—eventually, everything else faded away: the environment, the bodily sensations, thoughts, emotions. Everything disappeared except for what was unfolding in front of my eyes.

So, I spent many long moments in this state—not quite out-of-body but rather a no-body experience. It felt as though I became a point of perspective, suspended in space, entirely absorbed in the observation.

However, it did not resemble the dissociation of losing oneself in a book or deep work. Because although “disembodied,” I still retained a profound sense of spatial, situated awareness. I was there, acutely present, in the moment, but devoid of my typical physical form, thoughts, or emotions—just a singular point of awareness, spatially oriented toward the stage.

Perhaps experienced meditators might recognize this state from my description. But what’s remarkable is that it wasn’t at all self-induced. It required no effort. The performance itself drew that state out of me, or put me into that state.

Intermission: the “Nouveau Regard”

The experience of disembodiment during “Les jolies choses” was unexpected on two levels. To explain how and why, it’s helpful to understand the concept of “Nouveau Regard.”

Nouveau Regard (noo-voh-reh-gar) is a term we’ve invented (out of necessity) to refer to the experience of altered perception of something once familiar. Nouveau Regard is like a Reverse déjà-vu.

- Déjà-vu — I know that I experience it for the first time, but it feels as if I’ve experienced it before.

- Nouveau Regard — I know I have experienced it before, but it feels very different now.

An example of Nouveau Regard that many might be familiar with is visiting a house that you remember from childhood and feeling like it has become smaller (although in reality it’s your body that grew bigger). I am sure you might recall other instances of Nouveau Regard.

I’ve had a moment of strong sense of Nouveau Regard once during a ballet performance.

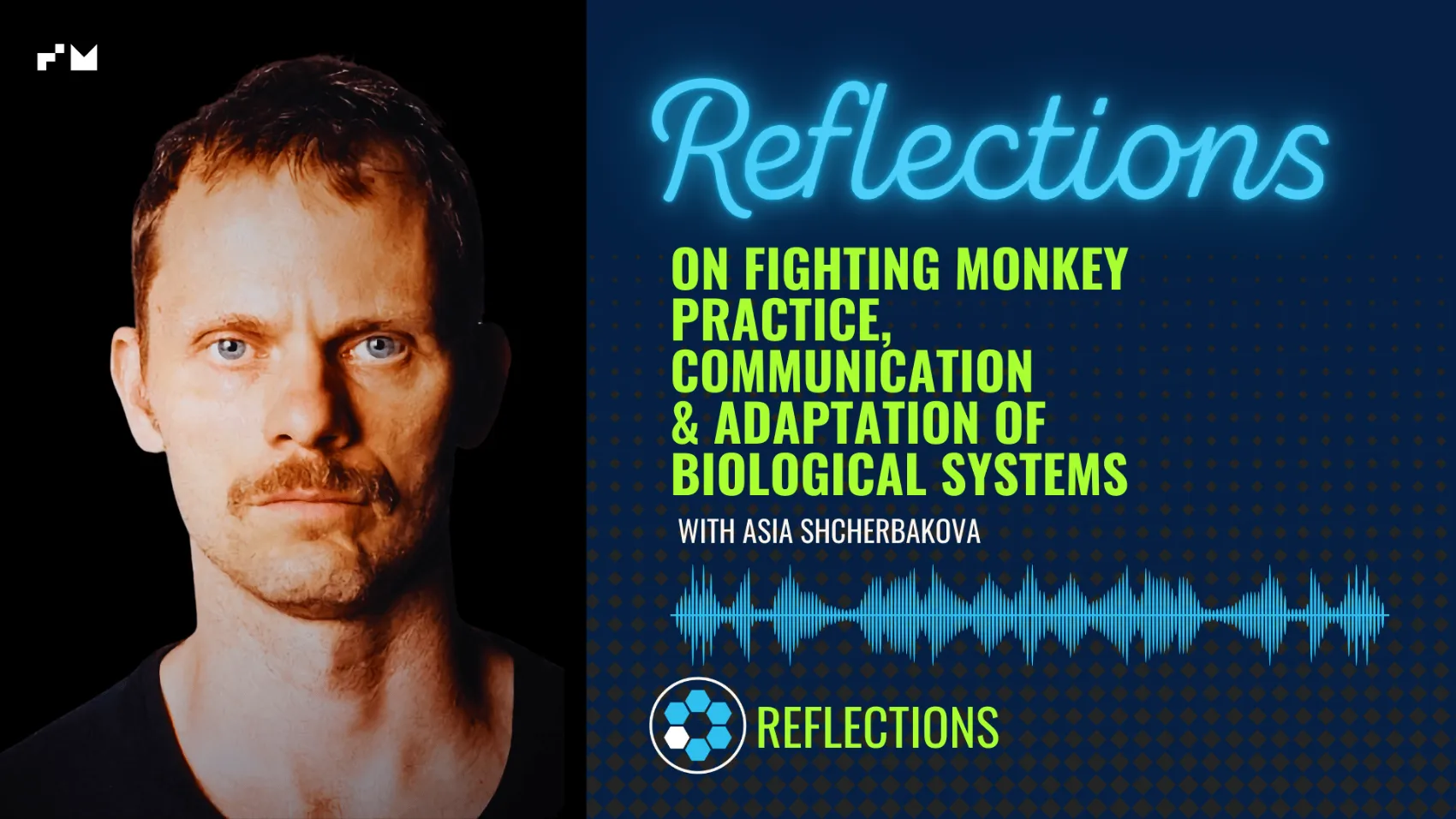

Growing up in a family of classical ballet enthusiasts, I saw many ballet performances. And though I appreciated those—I could perceive how the dancers’ movements were tied to music, recognize the precision of their synchronization, admire their flexibility, strength, and skill—it was predominantly a visual sensory experience. Then, I moved to Japan, where I eventually started working with my body, including Baseworks training, which led to noticeable shifts in perception. A few years later, I traveled to see my family and attended a ballet performance after a very long break. And suddenly, it was so much more than a visual experience! There was an additional layer of embodied simulation, as if my brain was trying to give me a sense of what it would feel like to perform the movements I saw on stage. For example, observing a dancer transition dynamically into an arabesque—quite an extreme position of limbs, which at the same time celebrates, or aesthetically follows, the functional tension lines of the human body—I wouldn’t just see it but also feel it in my body, like whipping splashes of muscular activation.

On a theoretical level, that altered experience made sense, aligning with existing research on the mechanisms behind our capacity for imitation. Focused physical training can increase bodily awareness and strengthen the brain’s ability to simulate movements observed in others, which is often linked to the activation of mirror neuron systems. Mirror neurons are neurons that fire both when a person performs an action and when they observe someone else performing the same action that has meaning to them. Meaning (understanding the intension) comes before imitation. In order to feel what others are feeling, we need to have a certain ability to do what they are doing. Increased familiarity or skill in a physical domain enhances our ability to internally simulate those movements, providing a more vivid sensory experience from observation.

The phenomenon of “perceptual learning” is often overlooked because it hides under the incremental but expected changes in the process of “skill acquisition.” Conversely, Nouveau Regard is an exciting experience that tells us, “Look how much you’ve changed!” So, we can use this experience as a metric to quantify our perceptual growth.

For me, that particular ballet performance delineated, with high contrast, two distinct eras of embodied experience: before and after Baseworks. Before, I would simply perceive movement of others as an external visual scene, and bodily sensations played very little significance in my life. After, visual perception has become enriched with heightened spatial and somatic sensitivity, actively coming to the forefront of my ongoing moment-to-moment conscious experience. And most importantly, this newfound spatiosomatic perception was intrinsically rewarding. In fact, this intrinsically rewarding and entertaining aspect of body awareness is where I see the greatest value of structured physical training—not just for professional dancers or athletes, but for everyone.

Of course, we can get used to anything, especially to something good. Over the past few years, I got used to this feeling of being “in the body.” Therefore, when the normally rich layer of embodied perception faded away during the “Les jolies choses,” leaving me in the “mind-only” state, I was very surprised. Was that also a Nouveau Regard? I’d say no, because the key feature of Nouveau Regard is that it is triggered by a familiar situation, and “Les jolies choses” wasn’t a “regular” performance.

So, what was that experience? Why did it happen? As you can imagine, I wasn’t wearing an EEG helmet to that performance to be able to say definitively. But I suppose it was such an overwhelming perceptual challenge that it required so much of my focus that it momentarily reset my now-habitual “embodied” perception, pushing it out of the sphere of conscious awareness, making me feel temporarily “disembodied.”

During the standing ovation after the performance, I was applauding the dancers and the choreographer for creating a piece capable of evoking such a profound cognitive shift.

What I later read

Naturally, after such an unusual experience, I was very curious: What exactly had I just witnessed? Who made it? What was their intent?

I discovered that the piece was choreographed by Catherine Gaudet and had earned her the prestigious Le GRAND PRIX de la danse de Montréal 2022. It was performed by Dany Desjardins, Caroline Gravel, James Philips, Lauren Semeschuk, and Scott McCabe. The music was composed by Antoine Berthiaume.

Catherine described her creative obsession during the process as aiming to construct “the most complex piece to memorize in terms of spatial references, both individually and as a group.”

This echoes conversations we overheard post-performance: how on Earth could the dancers memorize such repetitive sequences with such metronome-like music? But what I find even more interesting is that it actually makes sense how her intent translated into my unusual experience. While her goal wasn’t to induce a “mind-only” state of consciousness in the audience, it’s clear that the severe cognitive demands imposed by her piece inadvertently led me to that unique state.

Of course, even after reading multiple articles about this piece, I still have a lot of questions. There are many ways to create something that is impossible to memorize. However, something “insanely complex” (unfortunately) does not automatically become “so captivating you cannot stop engaging with it.” Usually, it’s the opposite. So, I find it mesmerizing how she managed to leverage perceptual and processing constraints, playing with the graduality of scene change and the proportion and dynamics of in-sync and out-of-sync movement. What an ability to capture and sustain attention! And of course, this wouldn’t be possible without the right sound. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a performance where the movements and the sound co-depended on each other so much. I am also wondering if the prohibition to film had more to do with the artists’ copyright or setting the conditions for an uninterrupted attentive experience.

Catherine shared that the dancers confessed to her about reaching

“another state of consciousness, a kind of second wind, as if time no longer existed, as if they no longer had the sensation of effort, as if they reached an ecstatic state.”

Observing the performance, this transformation was palpable, yet not entirely surprising. Dancers often enter altered states, one of the many reasons people are drawn to dancing. What struck me, however, was that this state of altered consciousness extended to the audience, at least in my case. “The pretty things” hijacked my perception.

By the way, the title, “Les jolies choses” (The pretty things), apparently, was selected to be intentionally deceptive. Catherine explained it like this:

“It doesn’t give any indication of what we’re going to see. It’s like telling the audience: this show will be harmless when it isn’t at all.”

I can only admire her cunning and cleverness.

Elaborating on the piece’s core concept, Catherine describes the performers as if they were

“stuck in an infernal machine to which they must respond. And what is paradoxical is that they also make the machine turn, they are the machine themselves. We are victims of our daily lives—we always feel caught in an infernal cycle of routines that we must accomplish—but at the same time it is we who make this machine work, who force ourselves to respond to it.”

Of course, these words very much resonate with the ideas that propel what we do in Baseworks. “Many actions in our lives are performed on autopilot, and even when we perceive our actions as conscious, there is a great deal of unconscious processes going on that we are not aware of,” as we say in our concept video explaining our focus.

According to Catherine Gaudet,

“there’s a nurturing anger that animates the piece; an almost adolescent moment of revolt; the desire to reclaim one’s autonomy and creative freedom.”

Ultimately, this piece feels like a powerful reclamation of agency amidst routine, and a statement to perceptual fluidity and adaptation.

Afterthoughts

I view that transition from a deeply embodied perception to an unanticipated, mentally engaging but disembodied experience during “Les jolies choses” as a striking illustration of the fluidity of normal perception; how it intertwines with physical training yet can be intriguingly interrupted by unique cognitive challenges posed by art.

What left a significant impression on me was the precision of the cognitive impact. When an anesthesiologist gives general anesthesia, they expect a very specific change in consciousness. When a person with photosensitive epilepsy sees flickering light, they predictably have a seizure. However, art rarely possesses such precision in its outcome. The public can be “moved” in either direction. As long as there is some reaction, the goal is achieved. Emotions are unpredictable. But Catherine Gaudet with her “Les jolies choses,” created with a goal of putting unprecedented cognitive demands on the dancers, achieves exactly what she aims for, with almost unsettling precision.

I never imagined I’d ever be commending a choreographic piece for inducing a “disembodied” experience, but I guess I am. It is the “power of art” in the most literal sense.

For those intrigued by the interplay between movement, cognition, and perception, if you ever have a chance to see “Les jolies choses” live, do so. The video absolutely doesn’t do justice to the piece and what it does to you. You have to be there to see it and feel it. Or temporarily stop feeling.

As an afterthought on the afterthoughts, I keep reflecting on the spatial residue of my dissociated body awareness. We distinguish between proprioceptive and spatial awarenesses for a reason. After “Les jolies choses,” I feel like we’d have to break down the spatial awareness further.